This is the next in a series of posts by recipients of the Career Services Summer Funding grant. We’ve asked funding recipients to reflect on their summer experiences and talk about the industries in which they’ve been spending the summer. You can read the entire series here.

This entry is by Rolando D.Z. Lyles

I spent my Summer in beautiful Miami, FL home of the cool ocean breeze, beautiful palm trees, and where the temperature is rarely below 70 degrees. However, my stay in the city wasn’t to just sulk in the sun. I was given the amazing opportunity to participate and contribute to the ongoing prostate cancer research lab of Dr. Kerry Burnstein at the University Of Miami Miller School Of Medicine. This opportunity was perfectly aligned with my future desires to become a researching professor. What made it better was that I have been interested in the research being conducted in Dr. Burnstein’s lab for the past 2 years and to secure a position in her University of Miami lab for a Summer was surreal for me. Furthermore, for this Summer in particular, it was important for me to be stationed in Miami because my father who is fervently battling with prostate cancer lives there and I don’t want to miss any opportunities to secure lasting memories with him.

I spent my Summer in beautiful Miami, FL home of the cool ocean breeze, beautiful palm trees, and where the temperature is rarely below 70 degrees. However, my stay in the city wasn’t to just sulk in the sun. I was given the amazing opportunity to participate and contribute to the ongoing prostate cancer research lab of Dr. Kerry Burnstein at the University Of Miami Miller School Of Medicine. This opportunity was perfectly aligned with my future desires to become a researching professor. What made it better was that I have been interested in the research being conducted in Dr. Burnstein’s lab for the past 2 years and to secure a position in her University of Miami lab for a Summer was surreal for me. Furthermore, for this Summer in particular, it was important for me to be stationed in Miami because my father who is fervently battling with prostate cancer lives there and I don’t want to miss any opportunities to secure lasting memories with him.

In the lab, I worked under the direct tutelage of Dr. Burnstein and Dr. Meghan Rice. Dr. Burnstein’s Lab and team not only welcomed me with open arms, but gave me my own project that intersected with the other projects that were being conducted by the other members of the lab. I wasn’t just sitting around doing menial lab tasks; I was actually contributing to the progression of science. My specific project involved 3D culturing prostate cancer cell lines on a special scaffold type that was acquired through a collaboration with another university. Unlike traditional

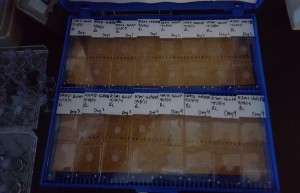

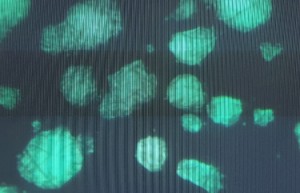

Burnstein’s Lab and team not only welcomed me with open arms, but gave me my own project that intersected with the other projects that were being conducted by the other members of the lab. I wasn’t just sitting around doing menial lab tasks; I was actually contributing to the progression of science. My specific project involved 3D culturing prostate cancer cell lines on a special scaffold type that was acquired through a collaboration with another university. Unlike traditional  3D cancer cell culturing scaffolds, this scaffold didn’t only allow the cells to grow in a more natural spherical form, but it prompted the cells to cluster into micro-tumoriods as would be seen only in in vivo conditions. My task was to first run experiments to determine how to optimize the growing conditions for different cell lines with varying gene knockouts. This then transitioned to conducting separate five to six day experiments which involved culturing, fixing, probing then staining these cell lines in order to use confocal imaging techniques to visualize tumoroid growth and make comparisons across cell populations. These scaffolds have the potential to revolutionize the personalized care sector of cancer medicine by creating an inexpensive system for culturing patient

3D cancer cell culturing scaffolds, this scaffold didn’t only allow the cells to grow in a more natural spherical form, but it prompted the cells to cluster into micro-tumoriods as would be seen only in in vivo conditions. My task was to first run experiments to determine how to optimize the growing conditions for different cell lines with varying gene knockouts. This then transitioned to conducting separate five to six day experiments which involved culturing, fixing, probing then staining these cell lines in order to use confocal imaging techniques to visualize tumoroid growth and make comparisons across cell populations. These scaffolds have the potential to revolutionize the personalized care sector of cancer medicine by creating an inexpensive system for culturing patient  biopsies and then tailoring specific treatments for improving that patient’s cancer by monitoring tumoriod progression.

biopsies and then tailoring specific treatments for improving that patient’s cancer by monitoring tumoriod progression.

Not only was this experience extremely enlightening but it has also helped propel my desires to continue my education after I graduate and pursue a doctorate degree. My time in Miami was spent just as would be expected. I spent my weekdays (an occasional Saturdays) conducting experiments in the lab. My evenings and weekends were spent with family enjoying quality time and embracing all that Miami has to offer. It was so fulfilling every day to wake up, get dressed and spend my day contributing to something that can potentially help better piece together our understanding of cancer, and save countless lives. One of the most gratifying parts of this Summer experience is that maybe one day in the future when the scaffolds are widely used throughout clinical research I can proudly say that I was one of the first researchers to ever work with them. As an undergraduate! Opportunities such as mine this past summer are what create tomorrow’s leaders.