Pre-health students — it has arrived! Feedback from our survey of Penn alums who started medical school in 2010 is here and available for your reading pleasure in the Career Services library and in the pre-health advising waiting area (aka, the places where we keep “the stats”). Here are some of the questions we posed to alumni:

- What do you wish you had known before starting the application process?

- Are there any specific courses you wish you had taken before starting medical school?

- What pre-medical experiences best prepared you for medical school?

- If you took time between undergrad and medical school, what did you do?

In addition to answering these questions, alumni generously provided detailed comments on about 36 individual medical schools with multiple responses for many schools (particularly Penn Med and Jefferson).

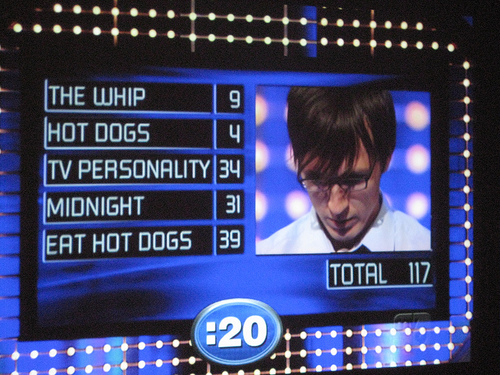

To warm up before reading the survey, get ready to hit the buzzer. Here is the question (insert dramatic silence): What do Penn alums, enrolled in their first year of medical school, wish they had known before they applied? Survey says! BING! TO APPLY EARLY! One third of those who returned the survey said they wish they had known to apply early. And so I say to you, “Apply early! It’s important!” Some other popular responses were: I wish I had known — applying to medical school is expensive…how important it is to know why you want to be a doctor…that medical school is very difficult…more about the curricula at different medical schools….

Alumni are always a great resource, those wise old Quakers! There’s a great deal of helpful information in the survey from many different voices and we appreciate our alums taking the time to share their experience and insight with us. Also, if you wish to connect with an alum, don’t forget the Penn Alumni Career Network, known as PACNet!